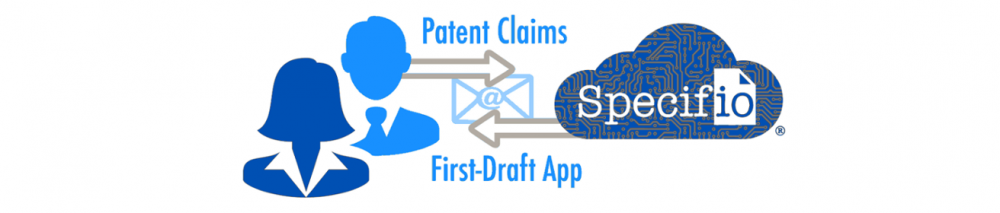

By Ian C. Schick, PhD, JD, CEO & Co-founder of Specifio (first posted on blog.specif.io)

For attorneys, gaining a practical understanding of technologies impacting the practice of law is no longer just an option. The rules of professional conduct in most US states now explicitly require a duty of technology competence, primarily so that attorneys can (1) determine whether and when to incorporate technologies into their own practices and (2) adequately counsel their clients on the benefits and risks associated with these technologies. In states that do not have the explicit requirement, the duty of technology competence is generally considered to fit implicitly within the existing duty of competence requirements. To be sure, the duty exists always, not just if an attorney decides to leverage technology in their practice.

In patent practice, the industry is experiencing an explosion in new technologies that let practitioners process their work efficiently with less errors, make data-driven decisions, and, overall, provide more value to their clients while respecting existing budget constraints. Indeed, tech adoption is becoming a competitive imperative for patent practices in order to cope with challenging economic and demographic trends in the hyper-competitive patent industry.

At the recent Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO) Annual Meeting in DC, the general session that opened the conference was titled “IP Automation – What’s Here Today, Not Years Away?” Representatives from private practice and in-house presented ways they are automating processes (e.g., docketing, filing, etc.) and automating patent preparation. The latter made a huge splash and dominated the buzz for the rest of the conference.

This article seeks to provide a practical understanding of document automation in legal, generally, as well as in patents, specifically.

What is Document Automation?

Document automation (also known as document assembly) relates to technologies designed to assist in creating electronic documents. Typically with some amount of human input, computers assemble text and other content into new documents. The text used to build the documents may be pre-existing (or “canned” such as boilerplate or templated text) or it may be computer-generated on the fly during the assembly process.

Document automation has been on the rise for years across many industries and is now becoming mainstream in legal. Stanford’s LegalTech Index lists about 250 legal document automation companies with more and more being added regularly. These companies serve virtually all areas of legal practice.

Benefits and Risks

The benefits of contemporary document automation generally far outweigh the potential risks. For example, document automation reduces labor needs for rote and mundane writing. Not only are these types of tasks detrimental to attorney job satisfaction, it is also wasteful to have a highly-trained practitioner performing tasks like this at steep hourly rates. Reducing burnout saves in recruiting and training costs. And reducing waste is essential for patent practices competing in today’s market.

Document automation has benefits beyond labor savings in document drafting. It reduces risks associated with human error. Because of this, and the ability to create more consistency between documents of the same type, document automation can drastically reduce the amount of time needed for proofreading. Since proofreading often rests with law firm partners or time-strapped in-house attorneys, time savings here is particularly impactful.

Some of the risks associated with document automation are the same as with any technology for attorneys, such as maintaining confidentiality and data security. Here, vendor transparency is critical so that attorneys can accurately assess these risks and counsel their clients accordingly.

Other risks relate to adoption and utilization. For example, failure to properly use or leverage technology where the costs are passed on to the client can potentially result in overbilling. If the cost being passed to the client does not reflect the full value that should be realized by using the technology, then the fees may be considered unreasonable from an ethical standpoint.

Another risk might be improper reliance on a technology due to a misunderstanding of its capabilities. For example, if an attorney relies on a technology to perform tasks A and B, but the technology is only designed to perform task A, then task B is either not being done at all or it’s being done inadequately, and potentially without the attorney realizing it.

A Framework for Understanding Document Automation

To have a practical understanding of how and to what extent a given type of legal document is or could be automated, it is useful to decompose the document based on content type. Legal documents generally have some combination of bespoke writing, mechanical writing, and canned text.

Bespoke Writing

Bespoke writing reflects the intellectual heavy lifting performed by attorneys while preparing legal documents. It often involves original analysis or disclosure on a unique fact set. This type of writing requires creativity and judgment. It is typically guided by the attorneys’ training, experience, and their knowledge of their client’s business and business strategy. Bespoke writing is too nuanced and context-dependent to be automated with existing technologies. This is where attorneys provide their primary value-add to written work product, which will likely remain the case for the foreseeable future.

The world’s most advanced system for natural language processing (NLP) and natural language generation (NLG), by far, exists between your ears. Expecting a machine to do bespoke legal writing is unrealistic with today’s technologies. Some cutting-edge technologies can generate text that may appear bespoke, but it can be unpredictable and nonsensical in the context of a specific legal document and underlying fact set. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs), for example, can create never-before-seen text, but only in relatively short spans (under 100 words). RNN plus neural bag-of-words (BoW) is used for real-time predictive text (e.g., Gmail’s Smart Compose), but is currently limited to just a few words ahead of a typist’s cursor.

Mechanical Writing

Mechanical writing is the traditionally rote and mundane parts of legal writing projects. This writing is usually driven by convention and/or by satisfying document requirements. It must be accurate and complete, but does not require significant mental work. Since the mechanics of mechanical writing are essentially repetitive across different documents of the same kind, this type of content in legal documents is ripe for automation.

From a technical perspective, mechanical writing can be automated with some combination of text transduction, text extraction, and text generation. Text transduction simply means turning one span of text into a different span of text. A common example of this in legal writing is propagating certain language throughout a document. If it were done manually, an attorney might copy and paste text into different parts of the document and then massage it so that the text reads appropriately for the different parts.

Text extraction relates to locating and describing facts to provide context and support within a document. In legal writing, extracted text may come from resources such as dictionaries, rules and statutes, encyclopedias, and other written bodies of knowledge. When used for document automation, relevant text (e.g., sentences or paragraphs) may be lifted from existing documents and used as content in newly generated documents.

Mechanical writing can include text generation such as summarization and data-to-text. With summarization, the most salient points of a larger document are distilled into a brief passage, which can be automated. One technique for automatically identifying pertinent terms in a document is known as “term frequency–inverse document frequency” (TF-IDF). This approach involves measuring, for each term used in a given document, the frequency in which the term is used in written language, generally, and then dividing that by the frequency of the term in the document itself. If a term is normally used rarely but appears often in a given document, the term is likely an important one.

When it comes to data-to-text, classic examples include weather reports, sports reports, and stock reports where noteworthy aspects of numerical data is automatically expressed with language. Because legal writing is not often informed by numerical data, data-to-text is less common in legal document automation.

Canned Text

Canned text is predetermined language such as boilerplate and template text. While this type of text is pre-existing, there is still an associated labor cost with manually identifying and locating appropriate canned text (e.g., in a template repository, old related documents, etc.). Different canned text needs to be properly organized within a document. It also may need to be adapted for specific projects, for example, by completing variable or conditional parts of the canned text.

Luckily, computers do a very good job of dealing with canned text for the purposes of document automation. A simple example is mail merge for letters and simple documents. Here, given some basic input information, a document with templated text is automatically completed by essentially filling in the blanks. A more complex example is contract assembly. With automated contract assembly, an attorney may identify a type of contract as well as the basic facts and terms. Based on that information, standard-language clauses are assembled into a draft contract document.

Different Legal Documents Lend Themselves to Different Automation Technologies, or Not at All

Depending on the type of legal document, there will be different ratios of bespoke writing, mechanical writing, and canned text. The ratio for a given type of legal document determines whether or not the document is a good candidate for automation and, if so, which technologies are best suited to automate that type of document.

At one end of the spectrum, contracts are dominated by canned text. There may be some amount of mechanical writing (e.g., propagating certain facts throughout the document) or bespoke writing (e.g, novel terms), but, by and large, contracts are mostly standard language. On the other end of the spectrum, memoranda are often primarily composed of bespoke writing where original analysis is being performed on a unique fact set. As such, they are generally not candidates for automation. Most legal documents, however, will fit somewhere in between where mechanical writing makes up a significant portion.

Document Automation in the Patent Context

A combination of statutory requirements and case-law-informed drafting conventions drive the contents and structure of patent applications. To be sure, a significant component of patent preparation includes bespoke writing where key concepts and nuances of an invention are described in a careful and strategic manner. The claims, obviously, fit squarely into this category, as do the background section and problem / solution statement.

A substantial component of most patent applications, however, includes mechanical writing and canned text. These are the parts that can be readily automated with currently available tools. In a patent application, mechanical writing may cover things like the title, field of the invention, summary, literal claims support in the detailed description, additional claim sets mirroring attorney-written claims, abstract, and basic drawing figures like those illustrating the environment in which the invention is practiced and method flow charts.

Other examples of mechanical writing may include lists of well-known examples (e.g., “Examples of types of material strength may include compressive strength, shear strength, tensile strength, and/or other types of strength.”), dictionary definitions (e.g., “Tensile strength is the resistance of a material to breaking under tension.”), and descriptions of well-known facts (e.g., “Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, and sometimes other elements.”).

Canned text in patent applications often includes things like boilerplate, stock figure descriptions, and stock definitions.

Conclusions

The duty of technology competence is now widely adopted in the US and applies regardless of whether tech is actually adopted. The threshold is not expertise, but rather knowing your limits and asking for help when appropriate so that you can make determinations about adopting tech in your practice and counseling clients as to the benefits and risks.

Document automation is becoming increasingly relevant to legal practice, particularly with patents. It helps practitioners avoid rote and mundane writing, which benefits them and their clients alike. With more and more products coming to market, it is important to have a practical understanding of document automation to have realistic expectations and appreciate the potential for your practice.

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and (1) are not provided in the course of and do not create or constitute an attorney-client relationship, (2) are not intended as a solicitation, (3) are not intended to convey or constitute legal advice, and (4) are not a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a qualified attorney. You should not act upon any such information without first seeking qualified professional counsel on your specific matter. The hiring of an attorney is an important decision that should not be based solely upon Web site communications or advertisements.