By Ian C. Schick, Ph.D., Esq. (first published in ABA Landslide Magazine)

- Ian C. Schick is founder and CEO of

Draft Builders and Specifio, fellow at Stanford Law School’s CodeX Center for

Legal Informatics, and chair of AIPLA’s Emerging Technologies Committee.

The manner in which patent documents are created has always been evolving—from handwritten patent applications to typescript, from typewriters to word processors, from dictation to auto-transcription, examples abound. The drive for better quality work product, enhanced efficiency, and improved work experience for practitioners has made this a continuous process since the beginning of the modern patent system.

Patent Document Preparation and Artificial Intelligence

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and the automation it brings have taken on an increasing importance in preparing patent documents.[1] Patent-specific, automated proofreaders, for example, which have now largely replaced the need for manual checking for minor informalities, first appeared over 15 years ago.[2] The first “dynamic document” patent editor (e.g., if a practitioner changes a label in a figure, corresponding text in the specification automatically changes accordingly) hit the market almost 10 years ago.[3] In the last five years, automated patent content generation (APCG or “auto-drafting”) has become commercially available.[4]

Current technologies in APCG are surprisingly precise but offer relatively limited solutions, typically focusing on only certain parts of a patent document and/or on only certain technology fields. However, unlike proofreading for informalities and synchronizing figure labels, the generation of content for patent documents hits at the heart of practitioners’ unique skills and value proposition. For this reason, and perhaps unsurprisingly, APCG has been met with frequent skepticism over efficacy and flat-out fear about job displacement.[5] Allaying these anxieties starts with a better understanding of where APCG stands today, how its development will likely progress into the future, and what that means for patent practitioners’ ever-evolving role in drafting documents.

In contemporary parlance, AI is essentially synonymous with automation for most contexts. AI is generally understood to describe “[a]n algorithm or machine capable of completing tasks that would otherwise require cognition.”[6] AI comes in three flavors: narrow AI (or weak AI), general AI (or strong AI), and super AI. Of these categories, it is only narrow AI that exists today and, by most accounts, is the only type of AI that will exist for the foreseeable future.[7]

Narrow AI describes a computer program that is good at performing a defined set of tasks (e.g., tasks associated with playing chess or Go or making purchase suggestions, sales predictions, or weather forecasts). In the broadest sense, today’s AI includes nonlearning systems that automate traditional human tasks (e.g., rule-based expert systems). Machine learning is a subset of current AI where hard coded algorithms are replaced by models trained on example input-output pairs to predict outputs for previously unseen inputs. Deep learning is a subset of machine learning that employs vast networks of artificial neurons. General AI is a purely hypothetical computer program that can understand and reason its environment as a human would. Also purely hypothetical, super AI describes a computer program that is much smarter than the sum of all human intelligence in practically every field.

Impact of Automation on Other Professional Services

Given the circumscribed capabilities of existing AI-based automation as well as the subtle nuance and broad contextual understanding required in drafting patent documents, the chances seem quite remote that AI will completely displace practitioners anytime soon. In fact, in many professional services industries, automation has led to more professionals rather than fewer. Take, for example, electronic spreadsheets in accounting[8] and computer-aided drafting in architecture.[9] In both cases, these disruptive technologies resulted in “a net positive for the industry with higher quality, higher efficiency, better access to services, and growth in the workforce.”[10] Will patent practitioners see the same in their industry with advances in APCG?

Motivation for Advancement in Automated Patent Content Generation

The motivating factors for advancement in APCG are straightforward and stem from a pronounced nonequilibrium in the U.S. patent marketplace. The last several decades have seen sustained growth in demand for patent services, with patent application filings and substantive official actions mailed up about 30% and 40%, respectively, over a recent decade.[11] Supply, in the form of active patent practitioners, has largely collapsed over the last 10 years, particularly in early-career practitioners who historically have served as important laboring oars in patent document drafting.[12] With rising demand and shrinking supply, a market at equilibrium would see rising prices. The reality, however, is a long-term downward trend in practitioner fees for preparing patent applications and office action responses.[13] For example, inflation-adjusted average fees to prepare and file a software patent application have decreased by about 34% over the past decade.

In the demand-supply-price equation, supply is the only thing the patent preparation and prosecution industry itself can affect. Since more patent practitioners will not arrive overnight, increasing supply means increasing per-practitioner document production without relying on adding significantly more practitioners. Efforts around this traditionally included using nonattorney practitioners (i.e., patent agents) and nonlicensed technical writers (e.g., patent engineers, technical specialists, etc.) for drafting work. Simply swapping out patent attorneys for patent agents or patent agents for patent engineers, however, is not a sustainable approach because it just taps another limited talent pool and maintains human inefficiencies (i.e., time, cost, and errors), but with lesser-trained individuals.

Patent Documents and Lean Production

A better approach to generating more substantive patent documents per patent practitioner requires treating document production as a manufacturing process that can realize the benefits of lean production principles.[14] In effect, a patent document preparation process should be viewed as a series of separate but interlinked subprocesses, with each subprocess being delegated to the most efficient (i.e., least expensive) resource without sacrificing work product quality or increasing chances for errors. If possible, each subprocess should be delegated to a computer (i.e., automated). If automation is not possible, the subprocess should be delegated to a “less expensive” human resource (e.g., nonexpert versus expert). And if that is not possible, the subprocess should not be delegated and, instead, be performed by a patent practitioner (i.e., the most expensive resource).

Content Type as a Framework to Analyze Roles in Document Production

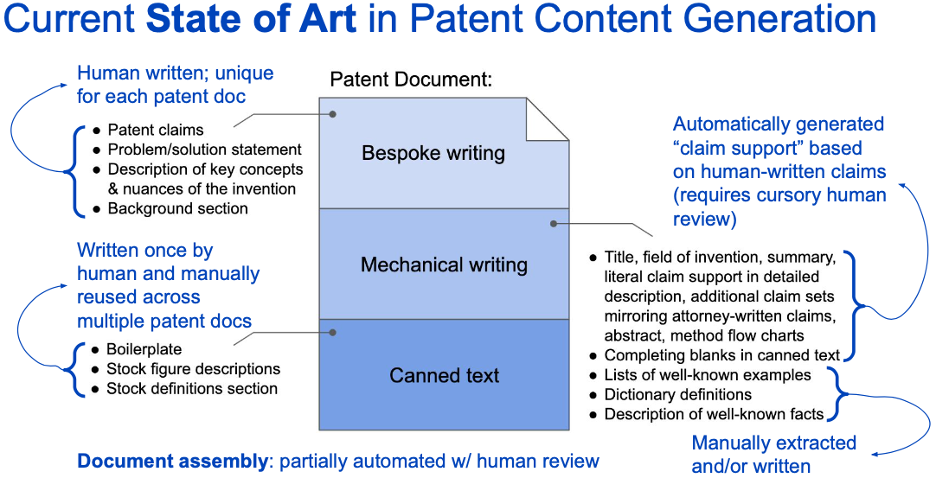

Without having to enumerate all potential subprocesses in drafting a patent document, the parts that can be delegated to a computer can be identified by analyzing the different types of content that exist in all patent documents; namely, bespoke writing content, mechanical writing content, and canned text.[15]

Generating bespoke writing content is where patent practitioners provide their primary value-add. This content reflects the intellectual heavy lifting performed by the practitioner preparing the document. It often involves original analysis on unique facts and is driven by creativity, judgment, strategy, experience, and contextual knowledge about the project at hand (e.g., assignee’s business objectives, known prior art, competitor activity, etc.). Bespoke writing content is too nuanced, context dependent, and consequential for wholesale automation. Examples of bespoke writing content include patent claims, problem/solution statements, description of key concepts and nuances of the invention, background section, and, for prosecution, claim amendments and arguments.

Mechanical writing content represents the rote and mundane parts of traditional writing projects. This content is driven by convention and/or by satisfying document requirements. It must be accurate and complete but does not require significant mental work. Traditionally, generating mechanical writing content includes a manual “copy, paste, massage” of claim language or text from a separate resource. For example, generating mechanical writing content includes propagating claim language throughout the specification (e.g., title field of invention, summary, literal claim support in detailed description, additional claim sets mirroring attorney-written claims, abstract, and method flow charts). It also generally includes manually extracting information from separate resources such as lists of well-known examples, dictionary definitions, and descriptions of well-known facts.

All patent documents contain some amount of canned text. Canned text is “predetermined language,” such as boilerplate, stock definitions and descriptions, and other reused content. It may be described as “static content” in that it is shared across multiple patent documents.

With content divided by type, it becomes readily apparent where opportunities lie for technical innovation and how practitioners’ role in patent document production will likely evolve and—some would say—improve for the benefit of the entire patent ecosystem (see fig. 1).

Figure 1

Generating Bespoke Writing Content

Unless and until general AI is achieved, generating bespoke writing content will remain the purview of skilled practitioners. At present, this content is entirely human-written and unique for each patent document. Technical advances in generating bespoke writing content will likely focus on accelerating practitioners’ ability to write, and not on replacing practitioners altogether as content generators. For example, predictive text (e.g., akin to what currently exists in Google’s Gmail message editor) may be implemented to provide suggestions for sentence completions, dependent claims, etc. In any case, however, human practitioners will remain central to generating bespoke writing content for some time to come.

Generating Mechanical Writing Content

Advances in auto-generated mechanical writing content have created substantial buzz in recent years, specifically around generating “claim support” for the specification based on human-written claims.[16] These tools, developed at both technology companies and private law firms, are accurate, instant, and reliable. They are accurate in the sense that they convert claim language into corresponding complete sentences that technically do the job of providing literal claim support. However, the auto-generated content can sound stilted and robotic when read.

Improving the readability of auto-generated claim support will accelerate adoption, but getting there will require advancements in claim language transduction and variety in surface realization. In other words, many, many sentence patterns should be used when generating text rather than only a few, as is currently the practice in commercially available systems. Take, for example, input claim language reciting:

- “wherein the shaft is made of a material including one or more of iron, steel, aluminum, or copper.”

Contemporary APCG systems might convert the example input above into a sentence that reads:

- “By way of nonlimiting example, the shaft may be made of a material including one or more of iron, steel, aluminum, or copper.”

Two key transductions occurred in generating the above output. The input language was converted to permissive prose (i.e., by use of “may be” rather than “is”), and the closed-ended list of the input claim language was converted to an open-ended list (i.e., by use of “[b]y way of nonlimiting example”). The same output sentence pattern, however, would generally be used in existing systems for any input having the same structure of the example input above.

A more advanced system might generate many potential outputs based on many different sentence patterns and suggest one at random or based on user preferences or other factors.[17] Continuing the illustration above, examples of such multiple potential outputs could include:

- “The shaft may be made of a material. By way of nonlimiting example, the material may include one or more of iron, steel, aluminum, or copper”;

“The shaft material may include iron, steel, aluminum, copper, and/or other materials”; or

“In some implementations, a material from which the shaft is made may comprise at least one of iron, steel, aluminum, copper, and/or other materials.”

Each of the above outputs reflects the same two transductions (i.e., permissive prose and open-ended lists) and is technically sufficient to provide the desired claim support, but, clearly, varying cadence and sentence structure should give a more natural sound to the reader. Auto-generation of claim support based on claim language has largely been solved in terms of efficacy, and readability will only improve. As such, fewer and fewer practitioners will spend time manually generating this kind of mechanical writing content, with client expectations following suit.

Aside from claim support, generating mechanical writing content includes extracting information from separate resources and massaging it into the document being prepared. Presently, this is a completely manual process typically performed by patent practitioners using dictionaries, technical references, encyclopedias, a law firm’s own past work product, etc. Future systems may automate extraction of definitions and descriptions of examples and well-known facts while respecting any copyright restrictions or requirements. For example, a custom (and perhaps automatically) built “dictionary” with topic-description pairs may be used to automate content generation, or at least accelerate it via suggested content. Content may be pulled from licensed resources, open-source dictionaries and encyclopedias (although attribution is often required), and the public domain (e.g., the patent corpus). In some cases, extracted content may be automatically paraphrased to avoid copyrights. Like claim support, this kind of mechanical writing will fade away from the task lists of practitioners, who will serve more as editors of this content.

Obtaining Canned Text

Utilizing canned text typically involves a practitioner manually searching through prior work product and copying parts into the document being prepared. Even though there is no fresh writing occurring, there can still be a significant labor cost. One existing system, however, takes an assignee name and a law firm name as inputs and extracts, from the published patent corpus, all the original templates used by the law firm in preparing patent applications for the assignee.[18] This potentially provides a great head start when preparing documents related to past work product. Future systems may add further automation to canned text utilization. For example, the automated extraction of boilerplate and other reused content may be further granularized. Some systems may automate suggestion and/or selection of appropriate reused language for a given project. Again, with canned text, patent practitioners will play a diminishing role and will act more as editors rather than content miners and arrangers.

Document Assembly

Systems exist today that partially automate assembly for patent documents. For example, some systems automatically populate a user-defined application template with auto-generated claim support, letting practitioners skip some of the minutiae of patent drafting. A future system may automatically build application templates or even first drafts based on practitioner input and preferences. Language synchronization may be implemented to ensure that, when the pieces are assembled in a single, well-formatted document, the language throughout is self-consistent. As a prosecution example, existing office action shell generators automatically populate templates with bibliographic information, current claims, standing rejections, etc., letting practitioners get straight to the amendments and/or arguments. Eventually, document assembly should be wrested completely from patent practitioners and delegated to nonpractitioner “document technicians” and/or to automation.

Conclusions

In sum, market forces are requiring patent practitioners to

move away from the traditional single resource (i.e., a practitioner), purely

manual document production. A content type framework is useful for envisioning

patent practitioners’ evolving role in drafting as workflows become more granularized

and patent document automation becomes more ubiquitous. In the foreseeable

future, practitioners will remain the primary drivers of value creation as they

craft bespoke writing content, perhaps with technology acceleration. For the

remaining content generation, practitioners will serve mostly as editors of

auto-generated and auto-assembled patent content. Individual practitioners will

be spared the low-value parts of drafting and will be capable of processing

significantly more patent work at the same or better quality as today. Even

with a smaller role per document and decreasing fees per project, if patent

procurement follows the trend of other automation-disrupted professional

services, demand for skilled practitioners will likely increase along with

improved access to services, quality, and efficiency.

[1]. Ian Schick, 10 Ways Tech Is Disrupting Patent Procurement, Law360 (May 17, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1159335/10-ways-tech-is-disrupting-patent-procurement.

[2]. Five Favorite Features of LexisNexis PatentOptimizer®, LexisNexis (Sept. 13, 2019), https://www.lexisnexisip.com/knowledge-center/five-favorite-features-of-lexisnexis-patentoptimizer.

[3]. TurboPatent: Helping Companies Protect Their Inventions without Breaking the Bank, Disruptor Daily (May 3, 2018), https://www.disruptordaily.com/turbopatent-helping-companies-protect-their-inventions-without-breaking-the-bank.

[4]. Richard Tromans, Meet Specifio the AI Start-Up Automating Patent Drafting, Artificial Law. (July 28, 2017), https://www.artificiallawyer.com/2017/07/28/meet-specifio-the-ai-start-up-automating-patent-drafting; see also David Hricik, Machine Aided Patent Drafting: A Second Look, Patently-O (Aug. 25, 2017), https://patentlyo.com/hricik/2017/08/machine-patent-drafting.html.

[5]. See Malathi Naya, AI Speeds Patent Process, but Robot Attorneys Still a Ways Off, Bloomberg L. (Dec. 31, 2018), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/ai-speeds-patent-process-but-robot-attorneys-still-a-ways-off; see also David Hricik, Augmented Patent Drafting and Ethics, Patently-O (June 8, 2017), https://patentlyo.com/hricik/2017/06/augmented-patent-drafting.html.

[6]. Ryan Abbott, The Reasonable Robot: Artificial Intelligence and the Law 22 (2020).

[7]. Cem Dilmegani, When Will Singularity Happen? 995 Experts’ Opinions on AGI, AIMultiple (Oct. 8, 2021), https://research.aimultiple.com/artificial-general-intelligence-singularity-timing.

[8]. See Jacob Goldstein, How the Electronic Spreadsheet Revolutionized Business, NPR (Feb. 27, 2015), https://www.npr.org/2015/02/27/389585340/how-the-electronic-spreadsheet-revolutionized-business; see also Lisa Cumming, After VisiCalc Revolutionized Accounting in the 70s, AI Is the Next Big Breakthrough, Blue J (Dec. 5, 2017), https://www.bluej.com/ca/blog/single-post/2017/12/05/after-visicalc-revolutionized-accounting-in-the-70s-ai-is-the-next-big-breakthrough.

[9]. See James A. De Lapp et al., Impacts of CAD on Design Realization, 11 Eng’g, Constr. & Architectural Mgmt. 284 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1108/09699980410547630.

[10]. The AIPLA/AIPPI/FICPI AI Colloquium Primer 3 (2019).

[11]. See Ian C. Schick, US Patent Filings: Peaking or False Peak, Faster Pats. Blog (Mar. 6, 2019), https://blog.specif.io/2019/03/06/us-patent-filings-peaking-or-false-peak; see also Ian C. Schick, Patent Practice 3.0, Presentation at the AIPLA Mid-Winter Institute 2020 (Jan. 30, 2020), https://blog.specif.io/2020/01/30/aipla-mid-winter-institute-2020-presentation.

[12]. Ian Schick, What a Maturing Patent Bar Means for the Industry, Law360 (July 9, 2019), https://www.law360.com/articles/1176373/what-a-maturing-patent-bar-means-for-the-industry.

[13]. Am. Intell. Prop. L. Ass’n, 2009 Report of the Economic Survey (2009), https://www.aipla.org/detail/journal-issue/2009-report-of-the-economic-survey; Am. Intell. Prop. L. Ass’n, 2019 Report of the Economic Survey (2019), https://www.aipla.org/detail/journal-issue/2019-report-of-the-economic-survey.

[14]. Ian C. Schick, A Production View on Patent Procurement, IP Theory, Winter 2020, https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ipt/vol9/iss1/3; see also Ian C. Schick, A New Paradigm for IP Practice 3.0, Faster Pats. Blog (Jan. 6, 2020), https://blog.specif.io/2020/01/06/a-new-paradigm-for-ip-practice-3-0.

[15]. Ian C. Schick, Understanding Patent Document Automation, Faster Pats. Blog (Oct. 8, 2019), https://blog.specif.io/2019/10/08/understanding-patent-document-automation.

[16]. See Ed Sohn, Biglaw Counsel with Biglaw Needs Develops the alt.legal Solution, Above the L. (Oct. 18, 2017), https://abovethelaw.com/2017/10/biglaw-counsel-with-biglaw-needs-develops-the-alt-legal-solution; see also David Hricik et al., Ethics of Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Drafting Legal Documents, 4 Tex. A&M J. Prop. L. 465 (2018), https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1080&context=journal-of-property-law.

[17]. See Sys. & Methods for Providing Adaptive Surface Texture in Auto-Drafted Pat. Documents, U.S. Patent No. 11,023,662 (filed Apr. 3, 2020), https://patents.google.com/patent/US11023662B2.

[18]. See Sys. & Methods for Extracting Pat. Document Templates from a Pat. Corpus, U.S. Patent Application No. 16/901,677, Publication No. 20200311351 (published Oct. 1, 2020), https://patents.google.com/patent/US20200311351A1.