By Ian C. Schick, PhD, JD, CEO & Co-founder of Specifio (first posted on blog.specif.io)

Annual patent filings appear to have leveled off at the USPTO in the first slowdown since the financial crisis of 2008. Is this a sign of a sustained plateau or even decline in annual filings? Or are the last few years just noise in an ever-increasing trend?

A look at the economics of patent preparation over the past decade may provide some explanation for the recent falloff in US patent filings. For example, consider the collision of these three trends: (1) stagnant fees for preparing patent applications, (2) increasing costs for law firms to generate patent applications, and (3) a labor shortage of junior practitioners to prepare applications. In this article, we will examine these market trends to offer a greater understanding of the current state of the patent-preparation market and where it may be heading in the future.

In the last decade, average fees for preparing and filing patent applications have remained quite stagnant. For software-related patent applications in particular, the average cost has been hovering around $11,000. It’s as if “buyers” and “sellers” of patent preparation are at an impasse over the value of drafting patent applications. This trend also coincides with the bi-annual release the AIPLA’s Economic Survey, which began in 2007 providing the first industry-wide visibility into fees charged by competing law firms (we’ll be looking further into this in a future blog post).

While fees have remained static, the costs associated with preparing patent applications, such as salaries and overhead, have been on the rise, slimming profit margins and creating significant cost pressures for law firm patent practices. The average annual salary for patent associates with less than five-years of experience, for example, has trended mostly upward since 2007.

Firms have responded to the revenue and cost trends in a variety of ways, but the most common reaction seems to be pushing the work down to individuals with lower billing rates. Increasing reliance on junior associates and patent agents for patent preparation, however, may be an unsustainable approach to cope with shrinking profits per app, which leads us to the third market trend.

The number of new patent practitioners has dropped by roughly 50% in the last decade. This is illustrated by the steady decline in the number of individuals passing the patent bar each year over the past ten years. According to the AIPLA Economic Survey, less than 7% of practitioners were under the age of 35 in 2017 compared to 13.2% in 2008, further demonstrating a decrease in early-career practitioners. Increasing reliance on this group of practitioners, due to shrinking margins for patent prep, is directly at odds with a shrinking pool of candidates.

Have the three market trends outlined above reached an equilibrium or are we at a tipping point for major change in the patent industry?

Are we at a tipping point for major change in the patent industry?

Taking a more historical view of patent filings in the US, a different picture emerges. Maybe we really are at the end of roughly three decades of steady growth. Alternatively, one could argue that annual patent filings should parallel the acceleration of technological innovation and, thus, these last three years are likely just a blip in an otherwise exponential increase in patent filings.

In some ways, the historical trend in US patent filings is reminiscent of Moore’s Law and transistor size. Many times since Gordon Moore made his famous prediction, the semiconductor industry feared that transistors had become as small as possible due to a “fundamental limit” only to see a breakthrough enable several more years of exponential increase in transistor spatial density.

Perhaps the patent preparation industry is awaiting a breakthrough to enable continued growth in annual patent filings to keep up with innovation. Gaining efficiency, in the form of lower per-app costs and higher per-practitioner drafting capacity, is clearly a requirement to continuing an upward trend in annual patent filings.

Greater efficiency could include optimizing human processes such as patent preparation and other pre-issuance activities. One could imagine future legislation simplifying the statutory requirements of patent applications to make preparing them more efficient. More immediately, however, human process innovation seems more likely to include growing adoption of outsourcing, offshoring, or other alternatives to the traditional law firm model for patent preparation.

Technical innovation provides another clear avenue to continued growth in annual patent filings. Several “PatentTech” companies have emerged in recent years in both document automation and patent process automation.

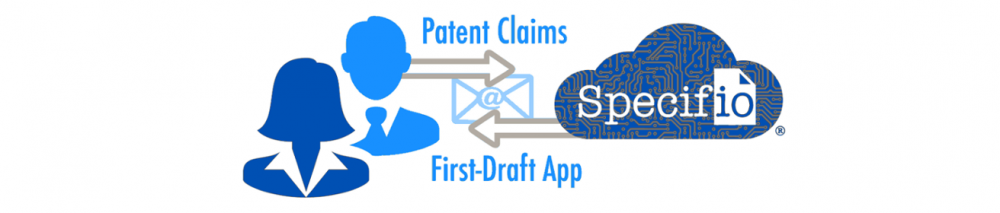

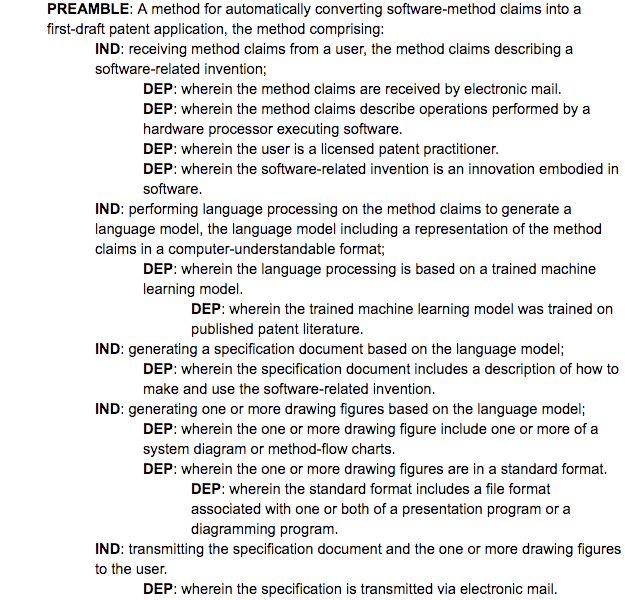

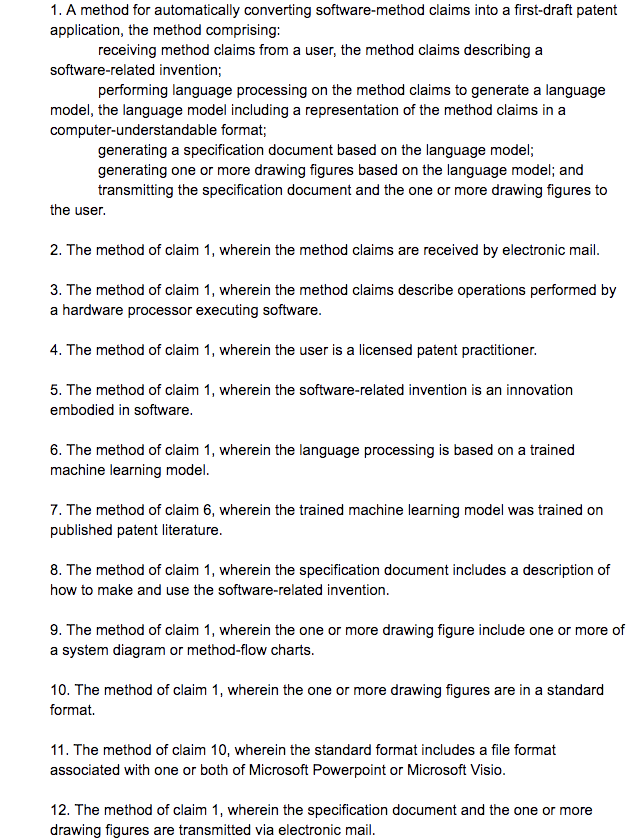

Leveraging AI, modern document automation goes beyond simple merges and form-filling. It can look at context, writing style, format and content requirements, and other characteristics to create or correct text. Existing examples of document automation include automated patent drafting, auto-generated patent figures, patent-specific proofreaders, and office action shell generation.

Process automation relates to non-writing tasks in the patent preparation and filing process. Examples of process automation on the market now include patent docketing, patentability searches, creating and managing information disclosure statements, and client reporting.

Ostensibly, the trends of stagnant fees, increasing preparation costs, and labor shortage could serve as threats to the patent industry, but they may actually be doing quite the opposite by driving PatentTech innovation. Regardless of the direction annual filings end up taking, advances in process automation and document automation are creating greater efficiencies within the industry. Practitioners and patent owners benefit alike with better work product and less rote and mundane work per application.

Data Sources:

- Fee and salary statistics: AIPLA Economic Survey 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017.

- Registration exam results and statistics: https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/patent-and-trademark-practitioners/registration-exam-results-and-statistics

- Filing statistics: https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/us_stat.htm

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and (1) are not provided in the course of and do not create or constitute an attorney-client relationship, (2) are not intended as a solicitation, (3) are not intended to convey or constitute legal advice, and (4) are not a substitute for obtaining legal advice from a qualified attorney. You should not act upon any such information without first seeking qualified professional counsel on your specific matter. The hiring of an attorney is an important decision that should not be based solely upon Web site communications or advertisements.